MEXICO CITY—I was in the bathroom when the shaking started, and at first I thought I had broken the toilet. Only two hours earlier the alarm sounded for an earthquake drill that takes place every year in memorial of the devastating 1985 terremoto. In a cruel form of irony, the city and surrounding communities were stuck on the same September 19th that 32 years ago took 10,000 lives. This tremor was not as strong, yet still collapsed 38 buildings and killed 360 people, including 219 in the capital and 28 children. Ordinary folks—many from a younger generation who grew up hearing stories of sacrifice—performed extraordinary acts of courage and service. Reminiscent of the citizen actions from ’85 that later overthrew seven decades of Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) rule, people are now asking if disaster will transform Mexican society once more.

As the ground shook, all I could think of was when would the trembling stop. At Fundación IDEA’s office on the 11th floor in the city’s core, I spider-walked to the center column where my colleagues had huddled in el triángulo de la vida and hoped for the best. After we evacuated, we emerged into a sea of chaos. The stench of gas filled the air, and people yelled not to smoke, others called loved ones and embraced in support. Walking home down Reforma toward my neighborhood of Roma Norte, I had never seen so many people in the streets. I went down Calle Colima to check on friends (who were fine), and saw the front of a building in shambles on the sidewalk. Destruction was everywhere and people reacted in full force.

Mexicans responded to the 7.1 magnitude earthquake (the second strong temor in 10 days) with expressions of compassion, grace and love. National solidarity plus social media became an equation for action. WhatsApp chat groups were consumed with activity, Centros de Acopio were overwhelmed with donations, and collapsed buildings were surrounded by volunteers in hard-hats and neon vests armed with shovels and buckets, anything that could be used to save lives. Acopio en Bici, avoiding traffic and traveling in silence around rescue sites, delivered supplies by biking hundreds of miles. Trendy restaurants opened their kitchens to feed hungry rescue workers and volunteers. And if you’re interested in helping, you can donate to Habitat for Humanity in Mexico or Los Topos, who formed after the ’85 earthquake and rescued numerous people. Yet while civil society and military support were welcomed, political actors and government assistance were met with suspicion.

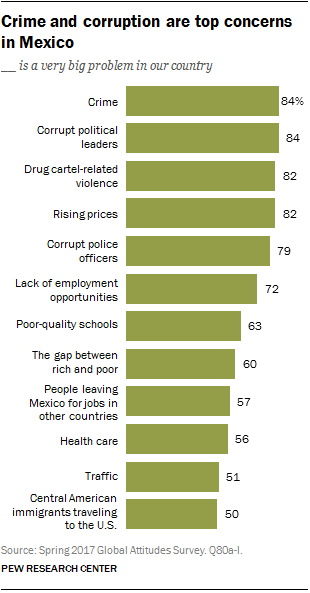

In the state of Morelos, the epicenter of the earthquake, the government has been accused of diverting aid packages to claim credit for new provisions. #RoboComoGraco, referring to the state’s Governor Graco Ramírez, trended on Twitter. Interior Minister Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, a powerful member of an unpopular presidential cabinet, was forced out of a rescue site and heckled with chats of oportunista. President Enrique Peña Nieto was booed as he inspected a damaged pueblo, and someone shouted out “grab a shovel.” Corruption, ineptness, and impunity are sadly assumed with this government. The Enrique Rebsamen school, that collapsed killing 19 children and seven adults, was ordered to close twice because of construction irregularities on its fourth floor where the owner and principal lived. Failure to enforce building guidelines and strict local supervision, enhanced after the 1985 earthquake, are now under investigation. My friend Roberto Velasco-Alvarez has called for an independent “Truth Commission” with international experts to investigate building code violations, and perhaps help rebuild a relationship of trust between civil society and government.

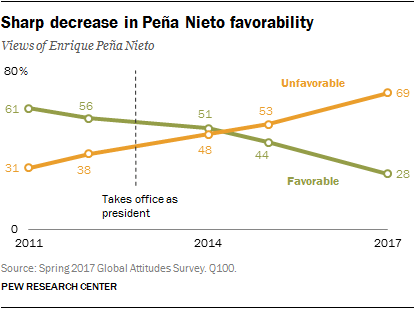

In my last post (published an hour before the tremors), I wrote about a recent Pew Center study that showed 85 percent of Mexicans are dissatisfied with their nation’s direction, with the vast majority disapproving of President Nieto and of U.S.-Mexico relations concerning President Trump. People are pissed off in Mexico, and after a disastrous earthquake, people are organizing. National solidarity and social media created a pressure campaign for political parties to donate part of the 6.8 billion pesos ($370 million) in public funds allocated for next year’s elections. With the public largely concluding the government has been missing in action, the fury and focus of their ire could be channeled toward political change.

Harnessing mobilized disaster relief toward organized political reform is a tall task with many respected skeptics, but Mexico might be in a unique moment. First, while Mexico is a different nation than in 1985, the economy has stagnated. Mexico now ranks as the world’s 15th-largest economy, but nearly half the population lives below the poverty line and real GDP per worker still remains below its peak in 1980. Second, Mexico transitioned toward a multi-party democracy, with free and fair elections since 1996 overseen by the independent Federal Electoral Institute (IFE), and this could give hope to disconnected citizens. Third, violence and insecurity are at record highs, and conflict with the drug cartels has cost 200,000 lives and left 30,000 Mexicans missing. These three factors are all interconnected and are top concerns for Mexicans.

Mexico’s vastly unequal society affects its economy, democracy, and security, and has created a vicious cycle, documented by the New York Times. People with resources buy private security and housing in safer, segregated neighborhoods. Not experiencing the effects of violence, elites do not apply political pressure for reforms that benefit everyone in society. The poor become preyed on by cartels, subjected to violence every day, and abandoned by the state. Research by Brian J. Phillips, a political scientist at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE), shows that local inequality is the best predictor of vigilante groups, as the poor seek security. This has led Mexicans to believe, “el contrato social se rompió” – the social contract is broken.

The central challenge Mexico must confront is its political economy of inequality. That is a fundamental problem and the means to repair the social compact between the Mexican people and their government. The history of 1985 suggests that people mobilized for disaster relief can be organized for political change. A renewed national solidarity and modern social media has the potential to harness the power of citizenship and collective action, and turn this moment of tragedy into a movement for equality.